Flamenco... the Madrid adventure

My fascination with the guitar began as a child, listening to pop records on TV and Radio. My mother used to play nice classical piano and could read music quite well but, somehow, I always felt that the guitar would be the instrument for me. I was a teenager living in Seattle when I got my first guitar. It was a cheap nylon-string Spanish type that I managed to persuade my Dad to buy me. Odd as it might seem, I made the decision to play left-handed, in spite of being naturally right-handed! For some reason, the guitar felt more comfortable with my right hand holding the neck and fingerboard instead of plucking the strings. A friend of mine in High School played left-handed, and so did Jimi Hendrix, so I thought ‘What the hell! ... let’s give it a go!’

My challenge then was to learn how to play it. Just being able to tune it was vital if any of my early efforts were to sound remotely musical, so I had to get help from somewhere. It wasn’t long before I met an experienced player who was kind enough to show me the basics of finger-style playing. In hindsight, my left-handed approach may have helped me at first. It made the chord shapes easier to learn and, yet, didn’t seem to hamper me too much with the necessary plucking techniques, such as arpeggios. So, with my friend’s help and encouragement, things started to come together, although I wasn’t really sure what kind of stuff I wanted to learn.

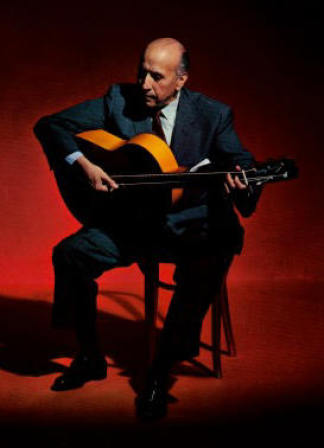

That all changed suddenly when I happened to hear some flamenco guitar on a TV programme. My curiosity led me to see a concert by the well-known flamenco guitarist Carlos Montoya at Seattle Opera House. I didn’t have a clue what he was playing or how he played it .... I was simply blown away by his skill, and the energy and vitality of his music. I had seen quite a few ‘live’ rock bands by then, but this was just one man and an acoustic guitar! So, despite my enthusiasm for the likes of Hendrix and Led Zeppelin, I decided there and then that I would definitely learn to play flamenco.

With the help of a few flamenco guitar records and an instruction book, the mysteries of this exotic and flamboyant music gradually started to unravel. Dad seemed pretty relaxed about my new obsession and just left me to get on with it, only interfering when he thought I might be annoying the neighbours! It would be fair to say that music wasn’t really his ‘thing’. As far as I remember, he only liked Mantovani (insomniacs, check him out!). Dad’s passions in life were his job as an engineer, and playing chess, both of which he excelled at. My mother (the musician in the family) was back in the UK at the time, so wasn’t able to offer any encouragement or feedback. I remember Mum saying to me once: ‘Your father’s hopeless! He’s got no sense of rhythm whatsoever’, or words to that effect. This all meant that any motivation had to come from within. Anyway, after six months or so, the shortcomings of my guitar (with its narrow fingerboard and feeble sound) were starting to become a handicap, so it was time to dip into Dad’s pocket once more.

My next box was a big step up in quality. For ten times the cost of the first one, I became the delighted owner of something that had more of the look, feel and sound of an actual ‘flamenco’ instrument. It was made by a Japanese luthier, Sakazo Nakade, and was about six years old, as I recall. The ebony fingerboard was the right width, and the back and sides were of a light-coloured wood, probably maple. I thought it was great, and practised on it day and night. In fact, it was probably one of the most important guitars I’ve ever owned ... simply because I had it at that crucial time when I was grappling with the rudiments of a complex and difficult playing style, and needed to feel that I was getting somewhere with it.

My passion for flamenco grew steadily over the months, and I was also developing a keen awareness of top quality flamenco guitars ....( look out, Dad!) I discovered a small-time guitar dealer not far away, who also happened to be one of Seattle’s foremost classical guitarists ... a guy called Bob Flannery. The first time I called at his very innocuous-looking shop, in an equally innocuous suburb of north Seattle, I was immediately struck by an unusual pungent aroma. This, I soon discovered, was from the various tonewoods used in making the guitars he kept there. In a small back room were guitar cases containing some of the greatest names in classical and flamenco guitars-making.

Bob had been busy exercising his Hernandez y Aguado classical guitar, and expertly rattled off a few short passages of something or other. The volume and tone of his guitar was astonishing ..... like listening to a piano! He gave me a small black and white catalogue to take home, which I’ve kept to this day. It features great Spanish luthiers including Ignacio Fleta, Arcangel Fernandez, Manuel Contreras, Hernandez y Aguado and Marcelo Barbero Jr. Bob’s business might have been small-time, but the guitars he dealt certainly were not!

Perhaps to my Dad’s relief, I didn’t end up having one of Bob’s lovely guitars. But what I did get from Bob was a collection of essential books on flamenco. Two of the titles were by the renowned American flamenco researcher and guitarist Donn Pohren. Donn fell in love with flamenco whilst carrying out military service in southern Spain in the 1950’s, and ended up writing the first English-language reference books on the subject, covering every aspect .... song, dance, guitar, history and so on. These books were like my passport into this vibrant new world. His opinions about the importance of expressing its true essence and spirit, as opposed to the meaningless ostentation of ‘tourist’ flamenco, influenced me from very early on. Donn preached the value of ‘less is more’ decades before the phrase was ever invented.

Two months after my 18th birthday I left Seattle to return to the UK. Reasons were partly personal and partly strategic. I wanted to visit Spain, and Dad’s job at Boeing enabled me to fly free of charge (and First Class!) on an Iberia Airlines ‘delivery’ flight to Madrid. The plan was to stay a while, buy a Spanish flamenco guitar, take some flamenco lessons, then hop on another plane to Heathrow.

I arrived in the centre of Madrid loaded down with a guitar case (the Sakazo Nakade) and a heavy suitcase containing my modest LP record collection, a few books, clothes, and anything else worth hanging onto. After an hour or so of tedious hassle I was able to dump my stuff at a hostal (cheap hotel) near the old Rastro district. Then, without any thought for food, drink or rest, I was off in search of Madrid’s main guitar makers, eager to see what they had on offer. Fortunately, most of them were within easy walking distance.

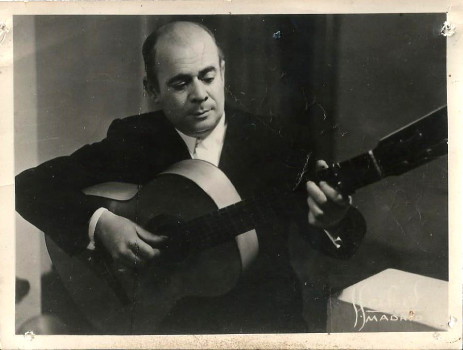

The addresses were in Donn Pohren’s book ‘The Art of Flamenco’, as were the names and addresses of a few guitarists who did lessons. Due to the Spanish tradition of ‘siesta’ (where businesses close their doors during the hottest hours of the afternoon), my routine was to practise guitar during the day, then wander off in the evening to look around, visit guitar workshops, and grab an evening meal somewhere. Very few of the locals spoke any English, so it was an opportunity to put my ‘college’ Spanish to good use. From Donn’s book I selected a nearby guitar teacher by the name of Juan Gonzalez. Juan (known by his professional name ‘Triguito’) was a bit of a legend in Madrid at the time. He was principal accompanist to the singers and dancers at Madrid’s main flamenco nightclub La Zambra, and a consummate player.

I remember Triguito as a shortish, slightly chubby guy with sparse grey hair. He lived in a tiny 2nd floor flat which he shared with his wife, whose name I’ve sadly forgotten. Thanks to my limited Spanish, we managed to get on just fine, and he straightened me out on quite a few things. Not surprisingly, it was all by demonstration .....theoretical explanation was pretty much out of the question! Originally from Seville in the heart of flamenco country, Triguito paid his dues as an accompanist to many flamenco legends, playing in tablaos (flamenco venues) and at juergas (informal parties) throughout Andalucia.

His wife used to make us coffee and, during breaks in the lesson, we would discuss (in our limited way) various guitarists. He was somewhat dismissive of my one-time hero Carlos Montoya, and rubbed his thumb and fingers together saying “tiene mucho”, meaning he was just very rich. When I asked him who was his favourite he instantly replied: “Paquito Lucia!” .... referring to Paco de Lucia, the rising young star destined to take the flamenco guitar world by storm during the 1970’s and 80’s.

At home, Triguito played a beaten-up Conde student guitar, and there were another two lying around in the kitchen where we did the lessons. They all had very worn strings. When I asked why he didn’t change them, his answer was simple: new strings would make the guitars too loud and would disturb his neighbours during siesta! His main guitar he kept at La Zambra, where he performed most nights. I got to see him play it on the nights that I went there to see him in action, along with a few other legends of flamenco song and dance. It was fascinating to watch.

It wasn’t long before I turned up at his flat with a nice new guitar. Well, to be more accurate, it was a nice old guitar .... a 1947 Sobrinos de Esteso, my first real flamenco instrument. In his book, Donn Pohren advises students to avoid new instruments and, instead, go for one that’s a few years old and played-in a bit. This one certainly fitted that description(!) and it was sold to me by the very man who had built it many years before, Faustino Conde. Faustino, who died in 1988, was the legendary head of the famous Conde Hermanos workshop, whose guitars have been used by virtually all the great flamenco guitarists of the last fifty years, including most notably ...... Paco de Lucia.

A day or two later, I took the guitar back to Faustino for him to fit new frets and lower the action. When I collected it, the charge for the work was 250 pesetas ... about £1.50! Impressed by the lovely smooth fingerboard, I asked him what tool he had used to achieve it. “Ah, secreto del profession!” he replied, no doubt wishing to heighten the mystique of his craft in the mind of a callow impressionable foreign kid. He then rather spoilt the illusion by giving the frets a final polish by rubbing the fingerboard vigorously with scrunched-up newspaper! Anyway, once my new toy was back in its case I was swiftly back to my hostal to stick new strings on, and give it a ‘go’.

Anyone would have thought that that was it, as far as my search for a guitar was concerned. Alas, life is rarely that simple. I had already visited the premises of top makers including Jose Ramirez, Arcangel Fernandez, Manuel Contreras and Felix Manzanero, as well as Faustino and his brothers. None of them (apart from Faustino) had any oldish second-hand flamencos for sale. But, for reasons I can’t remember, I called again at the Ramirez shop. Although the famous name of Jose Ramirez is mostly associated with classical instruments, his flamenco guitars are also up there with the very best, and were definitely on my radar.

I never met Jose himself because he used to spend most of his time at the workshop, which was at a different address. But on this particular visit, one of his staff showed me a brand new flamenco that was on offer at a greatly-reduced price. I remember it having a gorgeous rosette that is not often found on his guitars. Being a left-handed player, I couldn’t try it out, but it looked and sounded superb when the shop guy played it. He explained it was a perfect instrument apart from a small defect around the 12th fret. He pointed it out, but I couldn’t see anything wrong myself, and the price was 10,500 pesetas. I paid Faustino 17,000 for his Esteso ....hmmm.

This thought niggled me mercilessly over the next few days. I wanted that Ramirez but didn’t have enough money left after buying the Esteso. I wondered about asking Faustino to buy it back off me, but that would have been very awkward, and I decided against it. Instead, I managed to phone my Dad back in Seattle, but he declined to help me out this time, suggesting that I was being both greedy and hasty in equal measure. My arguments to the contrary were in vain, unfortunately. So I ended up bringing the Esteso into the UK, but if I’d known then what I’ve learned since about Ramirez flamenco guitars, I would have been tempted to conjure up some kind of sob-story for Faustino!

When it finally came time to pack my stuff ready to leave Madrid, I felt I’d achieved what I had set out for .... more or less. I had regrets about that Ramirez that I couldn’t bring home, and still do to this day. But, apart from that, I had enjoyed an intriguing and eventful few weeks in a major capital city steeped in history and blessed with a rich culture. And the late autumn weather had been dry and very pleasant, even though Triguito often greeted me with “Hola, hace frio verdad?” (Hi, it’s cold, don’t you think?) I’d say “Nah! Don’t be daft ... it’s lovely”.

The day before I left, I had my final lesson with him. He refused to let me leave without giving me one of his publicity photos as a souvenir. Triguito was unable to read or write properly, so his wife wrote a kind farewell message on the back, which he then graced with his signature. It was a somewhat younger man in the photo than the one sat before me. No doubt he had invested precious money having these done, presumably to mark his arrival in Madrid from Andalucia. Today, this small black and white photo is among my most treasured items of memorabilia. He was a truly memorable character, and a fine flamenco guitarist who really knew his art.